‘But why do you want to go to Ukraine?’

This was a question that both Tim and I got very used to hearing in the weeks after booking our flights to Kiev. Although there is plenty to do in the city of Kiev, the answer for both of us was simple: Chernobyl. Instead of helping people understand our choice, this answer seemed to baffle them even more. For days my ears rang with concerns about our health and whether the exclusion zone was safe. As a particularly nervous person and a self-confessed worrywart, these were all questions I had mulled over more than a few times. I was satisfied enough by the research I had done and was confident (at least as confident as I could be) that the trip would be not only interesting and educational but that I would also walk out of the exclusion zone alive and kicking. To all of those people who have no desire to visit the exclusion zone, allow me to show you what it is like. And for all of you as foolhardy as me who are wondering ‘how do I get there?’, there will be something for you too. But first, let’s get some background.

What happened at Chernobyl?

On 26 April 1986, reactor number 4 at the Chernobyl Power Plant exploded, leading to the worst nuclear accident in the world’s history. The effects of the disaster were massive. To give you some idea of the scale, the radiation released from Chernobyl was at least 100 times more than both atom bombs dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The surrounding area in Ukraine was completely devastated, including a large part of neighbouring country Belarus. In its entirety, the exclusion zone totals around 4,760km².

After the radiation was released, residents of the local communities were evacuated to non-contaminated areas whilst the liquidators tried to contain the radioactive debris and reduce the scale of the disaster. However, the Soviet Union was reluctant to reveal the full extent of the accident and many of those with homes in the disaster zone were led to believe that the evacuation was only temporary.

When the full extent of the damage had been realised and the radiation that could be contained had been, it quickly became apparent that Chernobyl and it’s surrounding areas were no longer safe for human habitation. It was soon announced that no-one was allowed to return to their former homes, although this did not stop everyone.

Many residents made the decision to resettle in the exclusion zone despite the danger, but of these individuals very few stayed there permanently, having realised the isolation and lack of prospects that the area held. However, there were some that the radiation would not drive out; mostly the older generation who were willing to take the gamble and live out the rest of their days in the homes they had spent their lives in. After some time, these people were granted permission to stay ‘semi-illegally’ and rather interestingly, the average life expectancy of these residents is much higher than the general Ukrainian population. For more on the lives of some that still live in the exclusion zone, check out the film ‘The Babushkas of Chernobyl‘.

Although there are obvious health risks associated with radiation exposure, the long-lasting effects of Chernobyl have been widely argued. Whilst there is undoubtedly a link between exposure to radiation and cancer diagnoses, the overall number of deaths resulting from Chernobyl is yet to be determined as many health issues are still developing in those who were caught up in the disaster.

What is it like visiting Chernobyl today?

It has now been thirty years since the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl and somewhat surprisingly, the place has continued to grow. Due to the lack of human presence in the zone, nature has begun to reclaim the area. Horses, bears and wild boar have all made the exclusion zone their home and appear to be thriving in the conditions, despite the constant danger of the radiation levels.

To visit the Chernobyl exclusion zone, you must be accompanied by a registered guide and with express permission. No-one under the age of 18 is allowed in and those that do visit must sign a consent form stating that they enter at their own risk. (Dark tourism can be pretty scary!) Entering the zone outside of these conditions is strictly prohibited but despite this, there are still some who enter illegally to explore alone. These individuals are commonly known as ‘stalkers’.

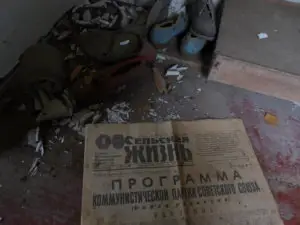

Officially, you are not meant to touch any of the objects in the affected areas as some of them have very high radiation levels. However, as you make your way through the exclusion zone, it is apparent that this advice is not always adhered to.

As you progress through the zone, you will see signs that warn of radiation hotspots and higher danger. Many of the tour companies that operate in Chernobyl will provide Geiger counters to visitors so that they can assess their radiation exposure throughout the day.

Pripyat in Pictures

The vast majority of people do not realise that the Chernobyl exclusion zone extends much further than the city of Chernobyl. The exclusion zone also covers the following settlements: Leliv, Kryva Hora, Zalissia, Kopachi, Yaniv and Starosillia. Interestingly, the vast majority of the photos of the zone you will see in the media, are not taken in Chernobyl but actually in the nearby city, Pripyat.

Before the disaster, Pripyat was a thriving city which was home to many of those who worked at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. A successful place which attracted the young, it made the ideal poster child for the cities of the Soviet Union. With so many young families inhabiting Pripyat, there was a large focus on leisure in the city, seeing the construction of stadiums, swimming pools and even an amusement park. Sadly the accident robbed Pripyat of all its potential and its facilities were left to fall into disrepair.

When the exclusion zone first opened to visitors it was possible to go inside the buildings in Pripyat, however, time has taken its toll and many of them are no longer structurally sound. The devastation in Pripyat centre means that you constantly have to check the ground for debris as glass and rubble cover the floor.

How do I arrange my visit?

If you are still keen on visiting Chernobyl, these are the things you need to know. One factor to be aware of is that it is worth booking way ahead of time. There are two reasons for this, the first being that the tours sell out very quickly in advance. You don’t want to fly all the way to Ukraine to then realise that you are unable to get onto a tour! The second is that as you are required to obtain legal permission to enter the exclusion zone and therefore your details will need to be submitted beforehand. Usually, the tour operators hand over your name and passport number up to a week early so make sure you leave enough time for the formalities.

As it is illegal to visit the zone without a guide, getting a good one is vital. We organised our day trip through the company Chornobyl Tour who were fantastic. We paid around £90/$122 each for our visit but it was well worth it. That fee included the medical insurance required, as well as permits, transport, lunch and the rental of a Geiger counter each for the day.

A final point of interest is to be aware that you will be given radiation checks at regular intervals throughout the day to monitor your exposure. Whilst your safety is a factor in this, the main aim is to prevent the smuggling of ‘Chernobyl artefacts’ so that they do not appear on the black market. In case you’re still curious, removing anything from the zone is, in fact, illegal and comes with harsh consequences, so I wouldn’t recommend you try it.

What effect does a trip to the Chernobyl exclusion zone have?

Contrary to what some people believe, it is completely safe to visit the exclusion zone. To anyone who still has reservations about visiting Chernobyl, I would urge you to put the experience into context. The radiation that you will receive throughout a day trip is roughly the same amount as you will receive during a flight of around an hour of a half. Physically, there is very little risk.

The disaster sites themselves can provoke a strong emotional response and I have found this to grow upon reflection of the trip. There have been many estimates about how long it will be before Chernobyl and it’s surrounding areas are suitable for normal human habitation again. Anything from 3000 years right up to 20000 years has been proposed by radiation experts. I find these estimations nothing short of heartbreaking. Whilst my visit to the exclusion zone was perfectly safe, knowing that there is now an area of the planet that we have succeeded in completely obliterating is something I find hugely difficult to reconcile in my mind.

What are your thoughts on visiting Chernobyl? Would you visit?

Massive thanks to my sidekick Timmy for using his creative prowess to take some of these amazing photos!

Love it? Pin it 🙂

Wow, you’re really exploring some curious places. I love it.

Thanks Byron! There is so much to learn from visiting places a little less conventional 🙂